January in flames, film, and farewells

assorted thoughts on the Los Angeles fires, David Lynch, Mulholland Drive, The Brutalist, and Nickel Boys

hello! This is not my long-awaited top 10 albums of 2024 post. That’s still coming! I’ve just had a busy month… so stay tuned.

in the meantime, though, I wanted to share a few things that have been on my mind this month: some of my thoughts on The Brutalist and Nickel Boys (both recent Oscar nominees), as well as some reflections on Mulholland Drive and David Lynch’s legacy. This is writing that I had done because I felt like it, without intending to put any of this on the SHA-STACK, but I think this is a good place for it to live. Much of this has also already been up on my Letterboxd.

before we get any further, I’m linking some donation pages below for a few charities supporting relief efforts for the devastating fires in Los Angeles this past month. I personally know a couple people who were affected—one of whom lost their entire house and community. The amount of loss is still unfathomable.

this has like at least 1,300 GoFundMe type things for individuals/families affected by the fires. It’s sorted by the percentage of funds raised toward each goal. My friend’s fundraiser is listed here as well, though he has thankfully already surpassed his target.

provides fresh meals through emergency kitchens, food trucks, local partnerships, etc.

offers shelter, meals, supplies, medical care, etc. Can click the red “Donate Now” button on the righthand side and then select California Wildfires 2025.

this isn’t a donation link, but instead a wonderful little two-page essay about the Santa Ana winds by California prophet Joan Didion, originally published in 1967 in the Saturday Evening Post. You can also find it as part of her 1968 essay collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem. The piece feels especially timely at the moment.

feel free to comment with any additional suggestions of ways we can all help. Thank you all! Please cherish everything.

sha

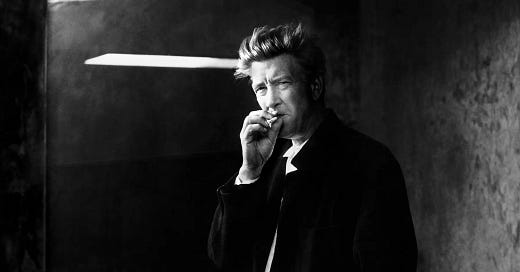

over the past couple weeks following David Lynch’s death, I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting and revisiting some of my favorite works of his. I watched Mulholland Drive with Alia, Blue Velvet with Nate, Zoe’, Ananya, Jon, and Alia, and the entire first season of Twin Peaks with Sahana. Theo, Sahana and I also watched that short film where Lynch interviews a monkey accused of committing murder. It’s even more absurd than it sounds.

stepping back into his worlds has been wonderful, but even more rewarding has been sharing the magic of Lynch’s work with so many of my closest friends. In each of these scenarios, I was the only one who’d seen the respective film before (besides that monkey one—none of us were prepared for that). Watching everyone’s faces shift between amazement, dread, terror, laughter, confusion and awe was so, so special. He’ll never leave us.

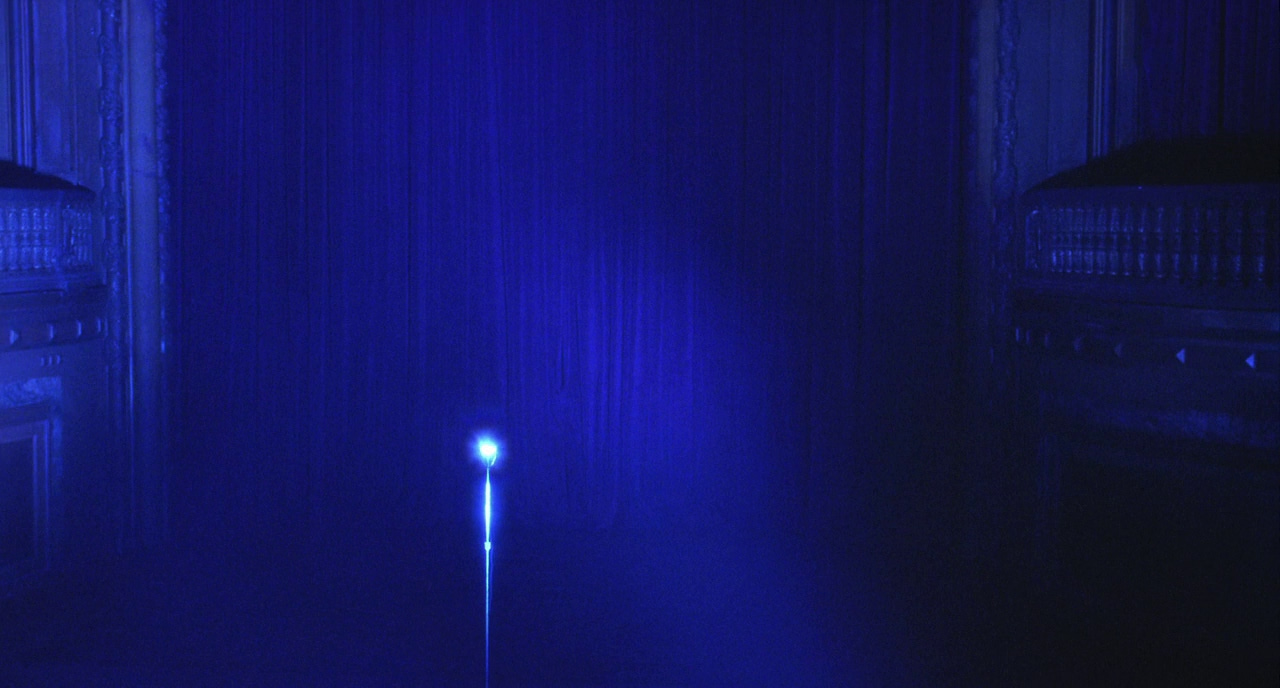

I’ve also put together the below playlist as a tribute to Lynch and the way his work makes me feel. It’s about 48 minutes, sequenced tightly, and meant to be experienced as one uninterrupted journey from start to finish. Its title is a fragment of a lyric from the first song, its description is a lyric from the second, and the cover image is a still from the opening shot of Blue Velvet. Four of the 13 songs appear in his films, but the rest all feel Lynchian in their own way. His own influences, as well as those he influenced, are all over it.

sonically, there’s a lot of ambient pop, Brill Building pop, doo-wop, and dark ambient, but I also wanted there to be some sense of lyrical and thematic continuity. I sequenced it so that some of the more off-putting moments crash directly into moments of real, undeniable beauty—just like in his films.

creating this playlist during one late night helped me elucidate my emotional connection to Lynch’s work, but I think listening to it might offer a new way of stepping into his world. Thank you to anyone who already has or will check it out—but if you do, just please, play it in order!! :-)

When a star falls (Apple Music)

Mulholland Drive

1/16/2025

David Lynch described his first arrival in his city of dreams like this:

"I arrived in L.A. at night, so it wasn’t until the next morning, when I stepped out of a small apartment on San Vicente Boulevard, that I saw this light. And it thrilled my soul. I feel lucky to live with that light.

I love Los Angeles. I know a lot of people go there and they see just a huge sprawl of sameness. But when you’re there for a while, you realize that each section has its own mood. The golden age of cinema is still alive there, in the smell of jasmine at night and the beautiful weather. And the light is inspiring and energizing. Even with smog, there’s something about that light that’s not harsh, but bright and smooth. It fills me with the feeling that all possibilities are available. I don’t know why. It’s different from the light in other places. The light in Philadelphia, even in the summer, is not nearly as bright. It was the light that brought everybody to L.A. to make films in the early days. It’s still a beautiful place.”

much of Mulholland Drive is bathed in this light. It glitters with an ethereal sheen—the sequins in Naomi Watts’ sweater catch and scatter it with her every movement and her perfectly white teeth dazzle and blind you every time she smiles. The outside environments buzz with color and energy by day and then get swallowed up by the blacks of the night. That deep, chilling rumbling comes when you least expect it, shakes the entire room you're in, and gets right to your core. And as the film stares the forces that pervert the Los Angeles dream square in the face, it forces you, like so much of Lynch's work does, to confront the terror lurking behind all beauty, the loss behind all hope, and the darkness behind all light.

the first time I saw Mulholland Drive was at IFC in summer 2022. I rolled out of my little twin bed in my barren dorm room on a blazing Saturday morning, took the A up to West 4th, ran into that AWESOME Chinese bakery right next to the theater, grabbed my pastries, and sat down in the smallest room in the cinema.

...

this was the first Lynch film I had ever seen, and so naturally, I walked out of the theater in a wild state of disorientation. The blinding brightness of that summer afternoon in the Village felt like an extension of Diane's dream. It was like my eyes were refusing to adjust.

the more I tried to make sense of the film right after watching it, the more my feelings remained frustratingly unresolved. But over time, I began to think about Mulholland Drive in more personal terms—as more of a deeply emotional experience rather than a puzzle to be solved. It became more about the things it made me feel and the moments in life that reminded me of it. The movie lingers, quietly embedding itself into your subconscious, showing up in fragments of your day.

and as my introduction to Lynch, it marked the beginning of a visual and sonic journey that has reshaped my worldview—the way I think about beauty and desire, the spaces we inhabit, the role of sound in cinema, the places films can take us, and even my aspirations in life (and my own LA dream). Few creatives have had such a profound impact on how I move through the world. Lynch's work comes back to me in those fleeting dreams that I can't quite remember but change me nonetheless, in the liminal unease of any space between spaces, or even in the thundering clatter of industrial machinery on the side of the street.

so now, I can’t help but believe that the light of Los Angeles—and of David Lynch—will forever be alive. No fire can take that away. On the day he died, I watched Mulholland Drive with Alia, who hadn't seen it before. I saw her experience all that confusion, laughter, fear, and enchantment that I had felt three years earlier. The “Sixteen Reasons” drop was just as magical. I have no doubt that Lynch will continue to inspire us, influence generations of artists, and illuminate everything that is beautiful and horrific outside and inside of us all.

THANK YOU DAVID LYNCH!!!!!

The Brutalist

1/14/2025

!! BEFORE WE BEGIN: DO NOT READ THIS IF YOU HAVEN’T SEEN THIS FILM !!

lots of discussions have been had around The Brutalist—its epic score that evokes the literal construction of buildings, Adrien Brody’s masterful performance as László Tóth (deserving every award he’s won), its dazzling cinematography, and the widescreen revival of the long-dormant VistaVision format. And then there’s the 3.5-hour runtime that doesn’t actually feel that long (which is to be expected—classic epic films often sustain their length far better than many plodding 2.5-hour slogs). Add to this its indictment of the American Dream (made abundantly clear starting with that early shot of the Statue of Liberty, but upside down), and the impressiveness of this all being shot in 31 days on a $10 million budget! Truly, wow. I don’t feel like rehashing any of this any further—on all of these fronts, The Brutalist achieves the greatness it so clearly aspires to.

after its perfectly placed intermission, though, as the film pivots into a postmodernist deconstruction of its classicist, Scorsese-esque tale of grand American ambition, a lot of questions get raised. While tumbling toward its beguiling conclusion, the film, naturally, avoids elucidating many of its ambiguities—things as simple as what happens to Van Buren after he heads to the Building at the end (I forget its real name but you know the one) are left unanswered.

to be clear—this ambiguity works in many ways. The unraveling of László’s dream begets the unraveling of the film itself. The dangling plot threads and the increasingly fleeting moments left for processing the film’s awful events create a chaotic narrative rhythm entirely unique to the second half of the film. Meanwhile, the visual style of this half—replete with surrealist drug sequences, Lynchian dream-dance scenes, and off-putting sex scenes—feels entirely fitting here. The two halves are like watching a tower meticulously constructed, only to witness it being spectacularly torn down. I really, really loved the film’s willingness to destabilize its own structure in service of its narrative goals, and it’s why I still mostly view the second half as a success.

BUT: here’s where the film’s tendency towards ambiguity becomes a problem, and unfortunately, this is where I have to talk about Zionism… The film has drawn criticism from some (my friends and others online) who interpret it as pushing the narrative that Israel is the only truly safe haven for Jewish people. And this interpretation does seem plausible—László escapes the horrors of the Holocaust only to face disillusionment and xenophobia in America. His wife Erzsébet and niece Zsófia join him, everything begins to fall apart, and Zsófia ultimately decides to move to Israel. Later on, after László accidentally causes Erzsébet to overdose on heroin, she feels she has no choice but to join Zsófia and her husband in Israel. Life in America isn’t working. Israel is the only place Erzsébet feels she has left to live. She asks László to join her, and he agrees.

except here’s the thing—I don’t think The Brutalist is actually pushing a Zionist narrative. In fact, it may very well be saying the opposite. Consider the ominous scene where László crafts his first chair in America, set against foreboding music and David Ben-Gurion’s 1947 speech about the partition of Palestine. The tonal dissonance suggests skepticism rather than celebration. Similarly, the scenes where Zsófia, and later, Erzsébet, resolve to move to Israel aren’t entirely given the narrative framing requisite of an endorsement.

what’s truly crucial here, though, is the wonky epilogue—a far cry from a “where are they now”-style shitty biopic ending. Remember—László Tóth is a man of fiction. Nothing in this film has to be shown to us. The film isn’t obligated to show us this man, decades later, old and decrepit at an architectural conference in 1980s Venice. And what’s absent here? Any depiction of László in Israel, his buildings there, or any indication that he even moved. The film could have confirmed its Zionist leanings with one single shot, but it deliberately, conspicuously, gives us nothing of the sort, and instead everything that indicates that László stayed in the U.S.

the epilogue finds Zsófia—who, by the way, is the subject of the first and last scenes of the film despite being mute for the entire movie, save the scene where she announces she’s moving to Israel—delivering a speech that reframes László’s work on the Building as a Holocaust allegory. She claims its extensive underground structure symbolizes László’s experience in tunnels in the camps, its windows represent Erzsébet’s experience in Dachau, and so on. She concludes by saying: “It is the destination, not the journey”—words she claims László told her struggling years in Jerusalem. Simply put, this is complete nonsense—the rest of her speech is entirely about the importance of László’s journey!

this ending is particularly odd for a film about how László wants his work to speak for itself (“is there a better description of a cube than that of its own construction?”). László’s work was never about metaphor or personal trauma. He passionately argues to the Doylestown residents that his religion and political ideology are irrelevant to the Building. When Van Buren asks, “Why architecture?,” László points to his old buildings in Budapest—structures that still stand after the war, inspiring freer thought and political change. His intent is for his work to endure and speak for itself, not to tell the story of his personal or communal struggles.

Zsófia’s speech is blatantly fraudulent. Her claim that the building symbolizes László’s struggles directly contradicts the practical, almost whimsical decisions we see him make onscreen. The ten feet of depth added to the underground? A petty act of defiance after being forced to remove ten feet from the top. The windows, supposedly representing Dachau? A spur-of-the-moment decision made on-site. László’s design philosophy prioritizes practicality and cohesion over elaborate metaphors or personal trauma.

even more telling, the epilogue avoids showing any of László’s supposed work in Israel. Instead, it highlights the many buildings he designed in the United States after the film’s main events, strongly implying he never left. His silent approval of Zsófia’s speech—smiling and clapping from his wheelchair—feels hollow, given his diminished awareness. The contrast between his earlier insistence that his work “speak for itself” and Zsófia’s overt politicization of it underscores the absurdity of the scene. The final blow comes in the form of the Italo-disco remix of the film’s theme that plays during the epilogue—a garish mockery of the original score’s grandeur, just as Zsófia exploits László’s work to push her Zionist narrative, stripping it entirely of his original intent.

the reaction to the film thus far highlights the fundamental problem with its ambiguity. The epilogue, which relies on viewers noticing the locations of the buildings on display, the contradictions in Zsófia’s speech, László’s diminished state, and the absurdity of the Italo-disco remix, ultimately plays things too safe. If László’s journey is meant to be anti-Zionist, the film’s depiction of its ending does little to ruffle any feathers. It’s hard to imagine any Zionists sat watching Zsófia’s speech and thinking, “Wow, I can’t believe she’s twisting László’s artistic vision to serve her own nefarious political motives!” …

I can’t help but wonder how the discourse around this film might have shifted had it leaned into the kind of boldly absurdist direction seen in The Substance here. Sure, maybe it would’ve felt out of place—but then again, everything about this scene already does.

just as László’s decision to leave his work open to interpretation made it vulnerable to exploitation, The Brutalist’s ambiguity in this critical moment undermines its own message. It dances around its point, making for compelling filmmaking, but poor agitating. By keeping its stance covert, the film risks letting the significance of its ending go unnoticed, leaving its message diluted and its audience adrift yet mostly pleased.

========

The Brutalist is also about cycles of abuse across generations, and I wish I saw more people discussing this. Zsófia is rendered mute due to some traumatic experience back in Europe, and Erzsébet mentions that something similar happened to her. It’s also implied that Harry abuses both his twin sister and Zsófia. Consider his interactions with his twin sister: the scene where he leans in and whispers something to her, and she tells him, very seriously, to stop; or where they argue behind closed doors and he says something like “Not as siblings, but as adults.” Then, there’s Harry’s intense reaction to Erzsébet revealing that Mr. Van Buren raped László in Italy—a revelation that feels like the final confirmation of what had previously been hinted at through framing and other visual cues: Harry himself was likely abused by his father, too. And finally, adding to this unsettling web of trauma is Mr. Van Buren’s Oedipal dynamic with his own mother.

I’ve seen a few criticisms of the Italy scene as being a grotesque, overly heavy-handed allegory for how capitalist industry treats those beneath it (or whatever), and while these criticisms still hold some weight, I just think that it’s important that we situate the scene within its context. Every major character in The Brutalist is either confirmed or heavily implied to be a victim of sexual abuse, and this trauma creeps around the film, an insidious motivating force for every character. It deserves far more attention.

Nickel Boys

1/2/2025

Nickel Boys is bursting with pure formal innovation on a level I haven’t seen in anything else all year—the first-person point-of-view is such a stunning, bold choice. What a way to adapt a novel. I do want to emphasize that since shooting in first-person is so rarely done, it's easy to point to that as the reason Nickel Boys feels so fresh, but the perspective never once felt like gimmickry to me.

the film validates its first-person viewpoint by tapping into what director RaMell Ross (insane that this is his feature length debut) has referred to as "the epic banal." These are everyday, fleeting moments—nothing life-changing, yet moments that, once witnessed, stick with us all the same. Watching your grandma's face when an old favorite song of hers comes on. Turning to glance at a new friend's reaction to something, searching for shared understanding in their eyes. Staring into your food, so as not to perceive the rest of your surroundings. Gazing into a television and seeing your reflection in the dreams of the space age, or of Sidney Poitier, or of Martin Luther King.

of course, there's still a plot here, but it's a plot constructed from memory.

if I had one critique of this perspective, it would be that there were times in which it limited the emotional resonance of the performances of the actors themselves—lines delivered by someone you can't see don't always land as hard. That said, what was missing in those moments was often superseded by the sheer power of the immersion anyway. The leads are both great actors, though, and I'd love to see more from them in future movies.

I've now seen a few comparisons being drawn between this and The Zone of Interest, and it makes sense—the two films take such radically different, but equally innovative, approaches to the depiction of horrific settings which have seen no dearth of coverage in cinema: the Jim Crow-era American South and Nazi Germany. It often feels like the two films are operating on different ends of the same set of spectrums.

The Zone of Interest eschews the typical film language and emotional cues of a Holocaust movie in favor of something closer to surveillance footage, piecing together just as much of a story through what is heard as through what is seen. Nickel Boys, on the other hand, is positively brimming with emotion—love, fear, joy, anger, despair, and hope all appear through the mundane objects we focus on and the faces we turn to. Meanwhile, The Zone of Interest—with its extensive usage of wide shots—rarely ever gives us a face to focus on.

both films also employ flashforwards that show physical remnants of their respective atrocities—thousands of charred shoes encased in glass, and unidentifiable human remains being unearthed from unmarked graves. The single instance of this in The Zone of Interest occurs at the very end, following a museum caretaker with no discernible personal connection to the story's atrocities. Conversely, the flashforwards throughout Nickel Boys all follow Elwood, the protagonist, in the present day. The specter of the school's abuses haunts him through the pixels on his computer screen—in every news article he reads and old photo he flicks through.

observing people coldly vs. becoming them, warmly.

hope you all have had an amazing month!!!! Until next time…